Every year, India sees around 10,000-15,000 babies being born with thalassemia major. And experts blame a lack of awareness and delayed testing.

A child born with thalassemia major is relegated to a lifetime of blood transfusions, which take an emotional, psychological, and economic toll on the family. Hyderabad’s Chandrakant Agarwal (74), a PhD scholar, who is currently serving as the president of the Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Society (TSCS) of Hyderabad — a role he has essayed for the last 13 years — experienced this firsthand, as he accompanied his granddaughter Nitya to hospitals across the country for her blood transfusions.

Having a front-row seat to the struggle compelled him to dedicate his life to coaxing India into relentless screening, which, he believes, can help in early detection and possible prevention of thalassemia.

“When Nitya was born, she was healthy. But at eight months, her skin started turning yellow, and we presumed it was jaundice,” Agarwal explains. Every treatment failed. One day, one of her doctors, observing the steadily dipping haemoglobin levels, advised a blood transfusion. “Within minutes of the transfusion, Nitya was fine! It was almost like a miracle,” Agarwal recalls the family’s astonishment.

Today, at 26, Nitya has routine blood transfusions every fortnight and chelation therapy to manage iron overload.

While her story makes a compelling case for how an efficient treatment modality lets a thalassemia major patient live life to its fullest, her grandfather believes there is no good reason any child should have to deal with something that can easily be prevented.

Understanding thalassemia

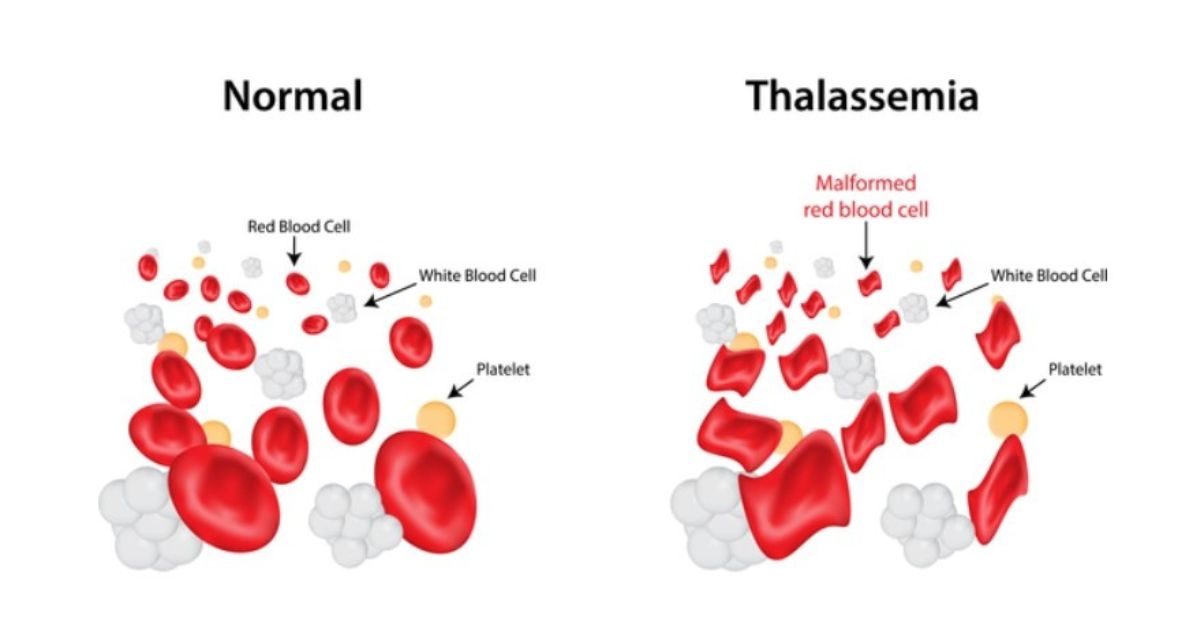

The blood disorder is inherited; it is passed down through genes and is characterised by faulty haemoglobin synthesis. This impairs the oxygen-carrying abilities of red blood cells, leading to fatigue.

Dr Suman Jain, a paediatrician, chief medical research officer and secretary, TSCS, cites one of the most common symptoms as irritability. “Low haemoglobin causes the child to become irritable, have low energy and become restless. The abdomen starts protruding, as the liver and spleen get enlarged.”

A major influx of patients at TSCS includes those referred from the hospitals in and bordering Hyderabad. At TSCS, around 60 blood transfusions take place every day. “And these are all free of charge,” Agarwal emphasises. However, he reasons that before getting to the treatment stage, ignorance colours most opinions when it comes to thalassemia. Parents believe that their child “will just get okay”. “They take them to a baba (godman), hoping to find a cure,” Agarwal adds. But in his tenure as president, he has found a way around this.

“Seeing is believing. So we put these parents in touch with other parents whose children have been battling thalassemia and who can vouch that blood transfusion helps.” A conversation paves the way for a better understanding. “When the parent sees their child feel better after a blood transfusion, they begin to believe that it is the right treatment,” Agarwal notes.

Another area where misunderstanding is rampant is the chelation therapy. A corollary of successive blood transfusions is the build-up of iron in the body. The excess iron needs to be removed.

Emphasising the importance of chelation, Dr Suman says, “It is absolutely important for the iron that is coming along with the blood being transfused to be removed. The serum ferritin needs to be less than 1000 ng/mL, but nearly 20-25 percent of our patients’ parents do not understand this. One round of counselling is not enough, and so we repeatedly tell them to get the iron chelation done.”

There are two ways to chelate the iron. One is oral methods — tablets ingested — or subcutaneous injections. “We first advise oral drugs, only if the iron levels are not being controlled, we start the child on injectables. The half-life of the drug in an injectable is short, and so it needs to be in the body for at least 10 hours. We monitor the serum iron levels every three months,” Dr Suman adds.

As for food restrictions, she does not advise her patients on any dietary modifications. “We tell them to cut down on meats and foods rich in iron. But considering that the major reason for iron build-up is the blood transfusion — every transfusion introduces 200 mg of iron in the body — diet does not make a big difference.”

Screening & testing: A way to future-proof India against thalassemia?

There are three kinds of thalassemias: thalassemia major, thalassemia intermedia, and thalassemia minor. People born with thalassemia major and the severe form of thalassemia intermedia require lifelong blood transfusions and iron chelation.

Those born with thalassemia minor are clinically normal.

Now, the conversation is slowly shifting to how the number of thalassemia major patients can be reduced.

As Manoj Jhalani, former mission director of National Health Mission, points out, “Approximately 30 million people are silent carriers for ẞ-thalassemia in our country and live a normal life, but the marriage between two silent carriers may result in their children having a serious disease, requiring regular blood transfusion for survival. Since only a limited number of patients can be cured by bone marrow transplantation from HLA-identical donors, prevention of the birth of an affected child appears to be the most feasible and cost-effective approach for control of this disease.”

The National Health Mission recommends carrier screening, genetic counselling, and prenatal diagnosis as a preventative approach.

This is where TSCS, led by Agarwal, steps in. A 2022 study by Genome Foundation and the Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Society (TSCS) found that four districts in Telangana were driving the average for high risk of Beta-Thalassemia. One of these was Mahabubnagar.

Would you believe that today, Mahbubnagar is leading the way in thalassemia control?

Agarwal explains how, following an MoU signed with the Collector of Mahbubnagar in 2022, 100 percent pre-natal screening was done. This means that every year, since 2022, every pregnant woman in Mahabubnagar has been screened — Agarwal credits the ASHA workers for this assistance — to check for thalassemia carriers.

If the pregnant mother is found to be a carrier of the thalassemia gene, the father is tested. If he too is found to be a carrier, the foetus is tested, and if found to be thalassemia major, the next step is counselling. “We counsel the to-be parents on the lifetime of blood transfusions the child will have to have, the difficulties of growing up with thalassemia, etc,” Agarwal explains. The focus is on giving parents the wherewithal to make an informed decision about whether to carry on with the pregnancy.

A former district collector of Mahbubnagar (wishing to remain anonymous) has commended the “extraordinary impact” of the project. Now, TSCS is looking to clone the model across India’s districts with government approval.

Testing is a pragmatic necessity, Agarwal shares, pointing out that it’s not only expectant parents who must be screened, but also families where there is a thalassemia major person. “In a case of a person with thalassemia major, we screened 78 family members of theirs, and 27 percent were found to be thalassemia minors.” Early screening means early detection, which can pave the way for early counselling and thus a preventative approach.

This could well be the contingency plan India needs to curb its thalassemia numbers.

But until then, your blood donation could save a child struggling with thalassemia.

This World Blood Donor Day, if you’d like to step in and help a child, check out the various camps TSCS is having here.

Edited by Khushi Arora